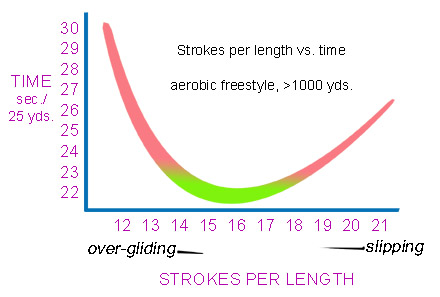

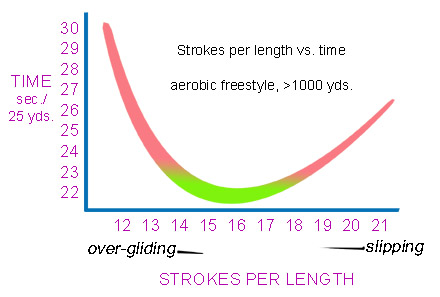

As your skills improve and you swim more efficiently, the number of strokes you need to cover a length will decrease. At some point, you will reach an optimum that gives you faster times with fewer strokes.

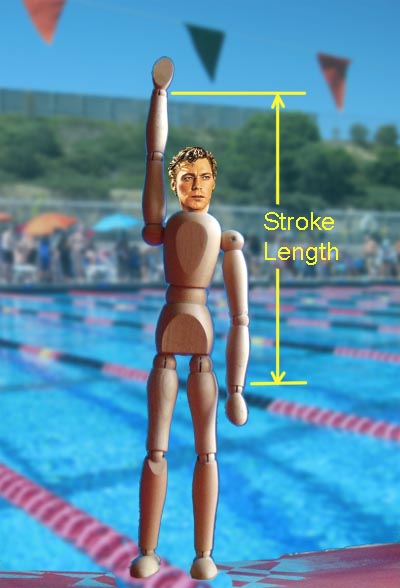

Johnny Stroker

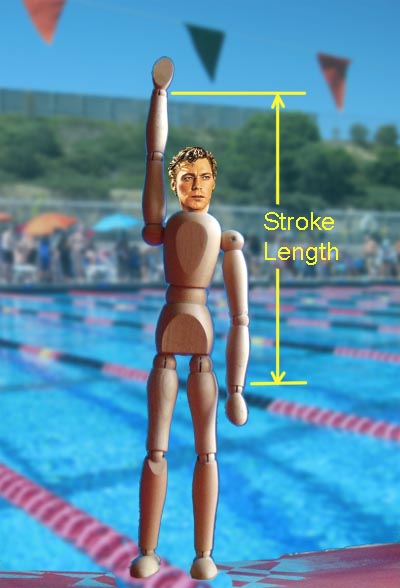

But what is a good starting point or baseline? A stroke is the distance you pull with one arm, i.e. it takes 2 strokes for a full cycle in freestyle. Though people come in different sizes and shapes, we can make a simple body measurement to determine your “custom” stroke length and calculate how many strokes would make a length with no slippage or over-gliding.

Measure

You can do this by standing next to a wall. Measure the distance from your arm’s reach above your head to the hip area, where you will give the final push-off for your stroke. Mark these two places on the wall.

You can stretch a bit for the reach, but keep your spine straight (remember that getting out of alignment will slow you down). Mark where your wrist is on the reach. Then do the same for the push-off hand position. The distance between is your Stroke Length.

For example, for “Johnny” the Stroke Length is 48 in.

The 25 yard pool is 900 in. long (25 yds. x 36 in.).

900 in. divided by 48 in. = 18.75 strokes per length, assuming no slippage and no glide between strokes. Now, count your strokes and see if you can make a length with 19 strokes or less.

How do you count?

Since we typically push off from the wall, it’s a matter of personal preference on how “strict” you want to be. You don’t want a big push-off and a long glide to give you an inaccurate baseline. This is not a competition, just a self-evaluation tool. Ideally, a 50 meter pool would be even better. I suggest counting the first stroke no further than a body length from the wall. Note that for the example above, the swimmer’s height is 70 in., meaning the whole 25 yds. is only about 13 body lengths!

The green area is the “sweet spot” of efficiency.

While counting, swim at an effort level that you can sustain aerobically (longer distance, minimum of 5 minutes continuous swimming). Concentrate on using a smooth, even arm stroke. As you lower your drag, you will get more distance for the same effort. See the video section for examples of the full stroke.

Conclusion

For each swimmer, there is a “sweet spot” (green area on the graph) where stroke efficiency maximizes performance for the effort. In general, taller, thinner swimmers will always have an advantage.

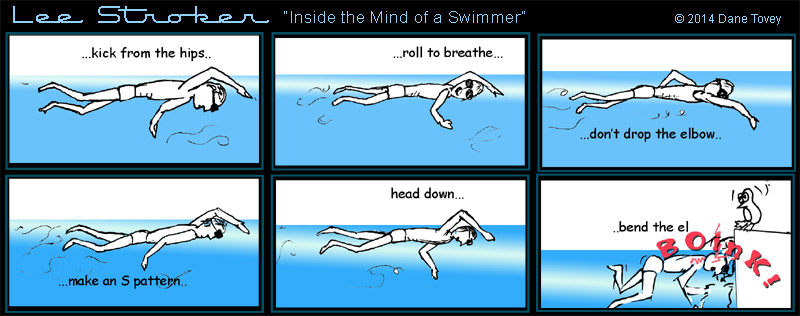

Over-gliding means you are not maintaining a consistent speed. Slipping typically occurs when your effort level increases and you become fatigued, causing stroke faults such as the notorious “dropped elbow.”